Indonesia is a highly dynamic market for the digital economy. Sales of online shopping, logistics and food delivery platforms in Indonesia have exploded during the pandemic. According to Redseer statistics, the number of online shoppers in Indonesia has increased from 75 million before the epidemic to 85 million, and the cumulative total amount of e-commerce shopping in 2021 will reach 40 billion US dollars, ranking third in the world after China and India.

At the same time, more and more Msmes are accelerating their migration to online digital platforms, with a total of 6.5 million Msmes in Indonesia migrating to e-commerce platforms from July 2020 to June 2021. According to Statistics Indonesia, 47.75% of businesses in Indonesia are using information technology for online marketing.

The digital economy has unleashed unprecedented growth potential in Indonesia, which has also made Indonesia a popular destination to go to sea. However, in this island of unlimited opportunities, policy uncertainty, stricter regulation, religious and cultural differences, data protection and other issues have become a secret reef that puzzles enterprises to operate in compliance.

This paper will focus on Indonesia's Internet regulatory environment, starting from three aspects: regulatory agencies, content regulatory laws and data privacy protection, and is committed to presenting the overall picture of Indonesian Internet regulation, helping enterprises avoid risks in advance and escorting security.

01 Setting of Internet Regulatory Bodies in Indonesia

Indonesia has established a series of Internet regulators and industry organizations with clear powers and responsibilities and clear division of labor, of which the Ministry of Communications and Information Technology and the National Cyber Security Agency are the main regulators.

The Ministry of Communication and Informatics (MCI) is the communications authority of Indonesia, with several departments responsible for the fields of communications, broadcasting, IT, and mass media. Among them, the Directorate General for Informatics Application is mainly responsible for the rectification of illegal content on the Internet.

The General Administration of Information Applications performs its regulatory duties mainly through user complaints and technical monitoring.

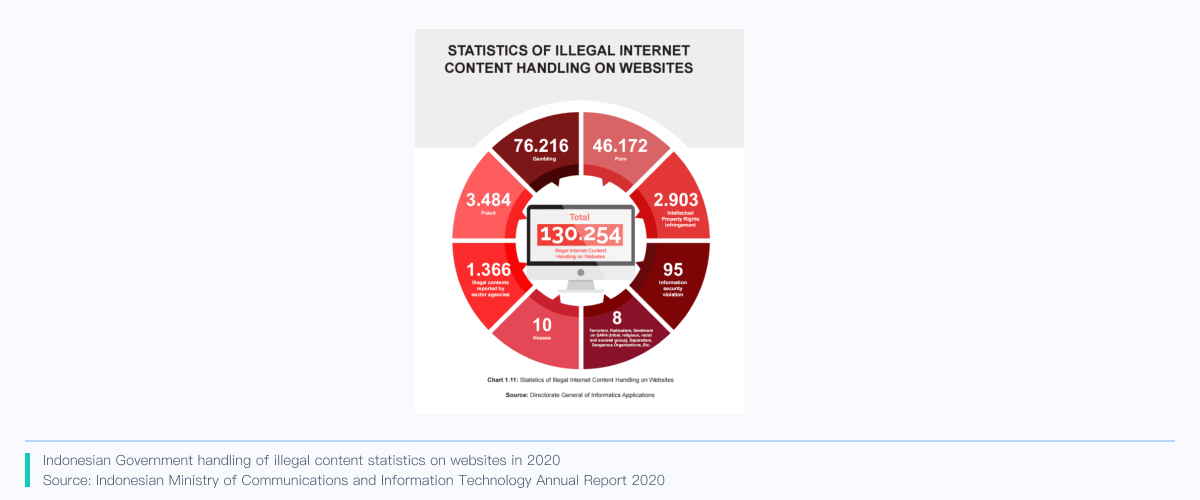

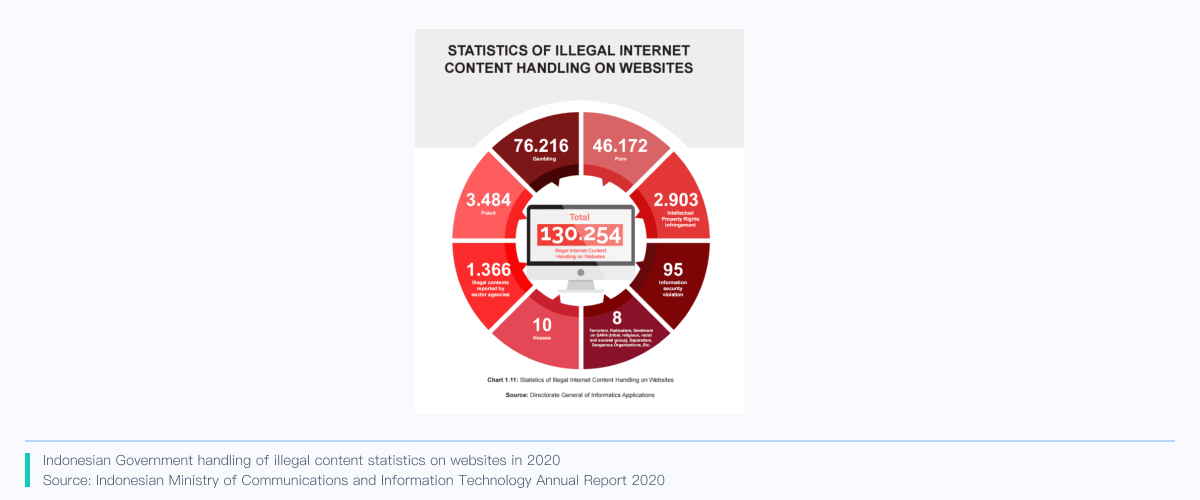

The number of user complaints handled by the General Administration of Information Application every year is increasing year by year. It handled 6,357 complaints from users about bad websites in 2016, a figure that soared to 60,000 in 2017. In 2020, MCI handled more than 130,000 complaints about illegal content on websites, double the number in 2017.

According to MCI's official annual report, from 2017 to 2020, in addition to the soaring number of complaints, the types of complaints have also changed greatly. The top three offending content complaints in 2017 were pornography, racial discrimination and defamation; By 2020, as can be seen from the figure below, the top three complaints have become gambling, pornography and fraud, of which gambling and pornography account for 94%, jumping to the two major bad Internet content with the highest complaint rate in Indonesia.

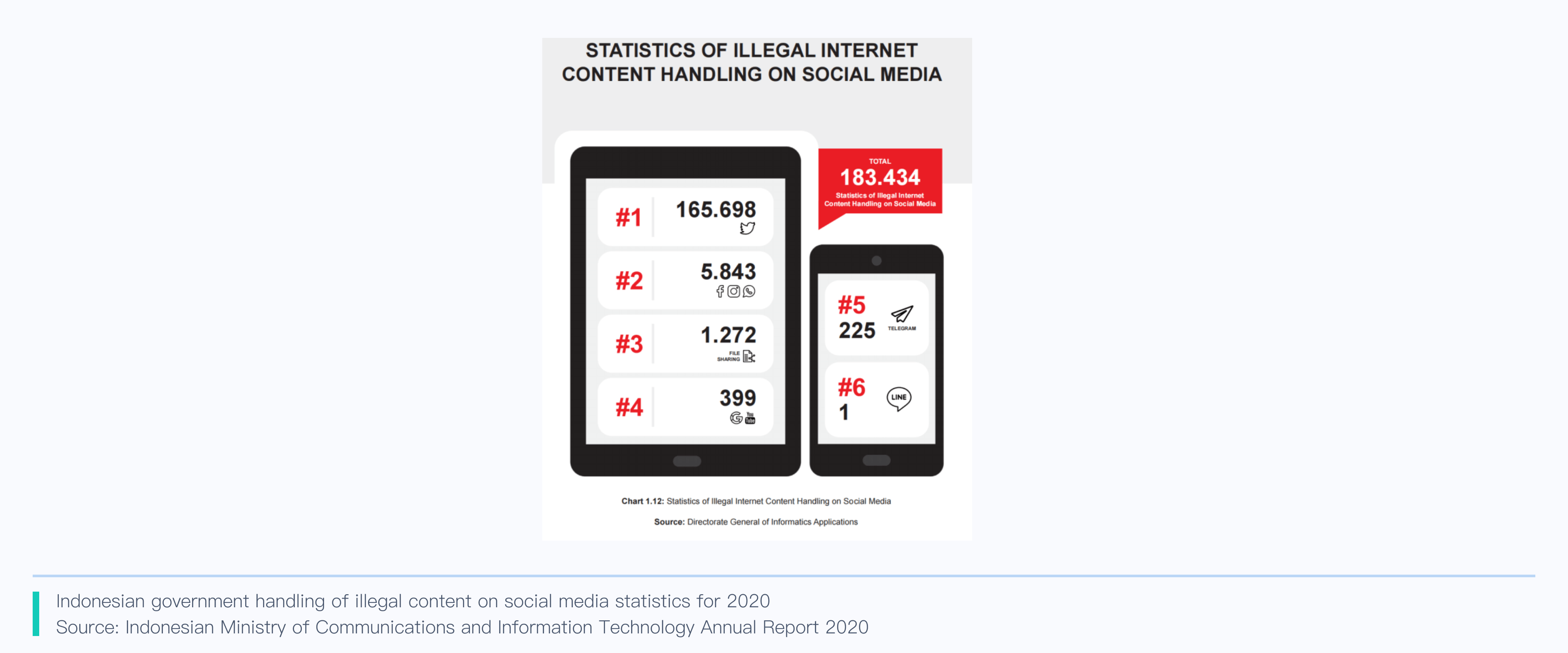

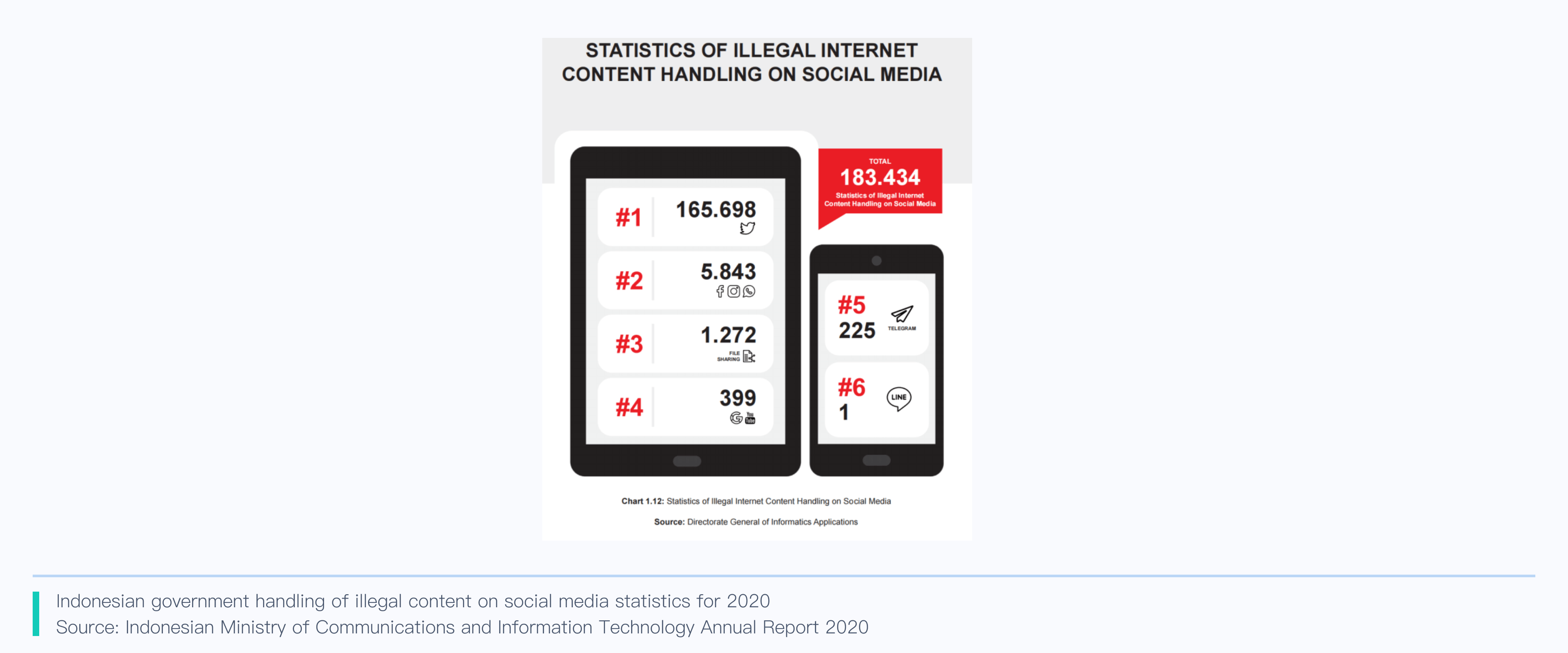

In addition to websites, social media is also a target of the General Administration of Information Applications. In 2020, MCI handled more than 180,000 complaints about bad content on social media.

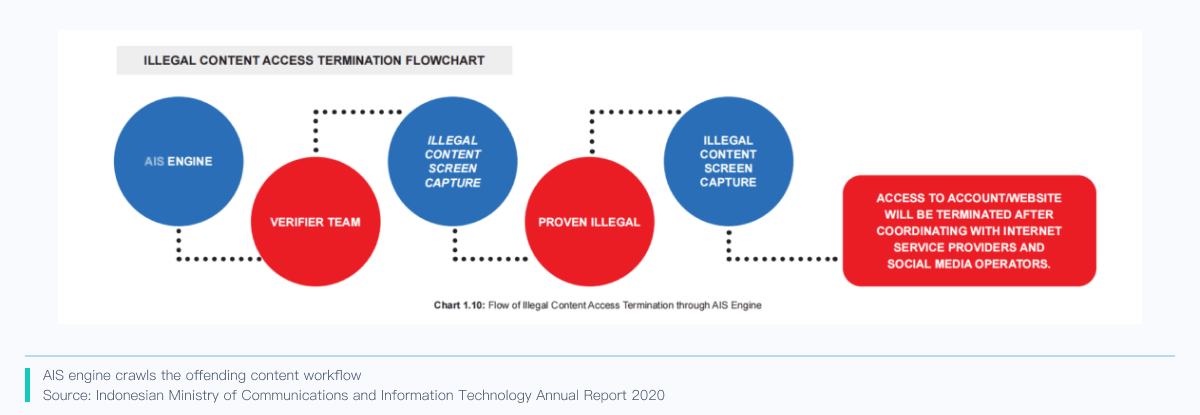

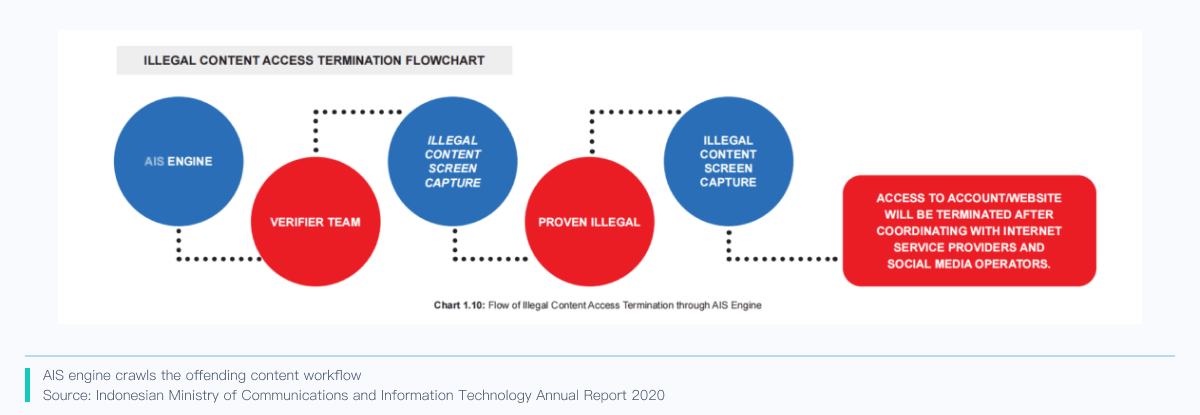

The General Administration of Information Applications will also take the initiative to investigate and punish illegal content on the Internet, and its censorship methods include network inspection and technology crawling. In January 2018, the General Administration of Information Application officially used the AIS engine to actively crawl the illegal content on the network platform through keyword search.

In addition, every year, MCI also develops KPIs for the investigation and punishment of illegal content, such as in the 2017 work report, the number of network inspections and negative content blocking processing in 2018 is set at 60,000.

National Cyber Security Agency

The National Cyber and Encryption Agency (BSSN) is the only other government agency in Indonesia with regulatory authority over the Internet. In 2017, the Indonesian government announced the creation of a new "National Cyber Security Agency" to tackle religious extremism and fake news online. The National Cyber Security Agency is a non-cabinet government agency, but its director is a government minister. The director is Djoko Setiadi, a former head of the State Secrets Protection Agency, whose main responsibilities include shutting down terrorist networks and tackling hate speech online.

Indonesia's Internet regulatory body also includes the Security Incident Response Team (ID-SIRTII) of the Indonesian Internet Infrastructure/Coordination Center, which was established by the Ministry of Communications and Information Technology in 2007. ID-SIRTII's mandate focuses on raising awareness of information technology security, prior monitoring, prior detection and prior warning of threats in telecommunications networks, especially the Internet.

02 Indonesian Internet Regulatory Legislation System

The rapid development of the digital economy in Indonesia has also prompted the country to accelerate legislation related to Internet regulation. Up to now, Indonesia has legislation covering cybersecurity, e-commerce, Internet content, data protection, etc., and the above-mentioned regulatory authorities are responsible for supervising law enforcement. The following highlights three major laws and regulations governing the Internet in Indonesia: the Electronic Information and Transactions Act, the Anti-Pornography Act and MR 5.

Electronic Information and Transactions Act

Indonesia passed the Electronic Information and Transactions Law (EIT Law) in 2008 and amended it in 2016. The EIT Law, Indonesia's first to regulate banned content online, was controversial when it was introduced, widely seen as restricting freedom of expression.

Articles 27, 28 and 29 of the EIT Law stipulate that the following shall not appear on the Internet: against propriety, gambling, defamation, blackmail or threats, spreading false or misleading information and causing damage to the rights and interests of consumers, spreading hatred or disinformation against individuals or individuals because of ethnic, religious, racial or social groups, and sending violent threats and intimidation messages to individuals.

The EIT Law also sets strict punishment conditions for those who violate the law. Using electronic means to send defamatory information or documents is punishable by up to four years in prison and a maximum fine of 750 million rupiah (about $50,000).

The EIT Law has a very broad definition of prohibited content on the Internet, which makes it the most frequently invoked legislation in Indonesia to enforce objectionable content on the Internet. The most famous case was in 2009. When Prita Mulyasari wrote an email complaining about her experience at a private hospital on the outskirts of Jakarta, it was forwarded to an online chat group. She was subsequently arrested on charges of online defamation.

In 2008, Indonesia passed an Anti-Pornography Law, which has been controversial but has gained the support of many Muslims.

The Anti-Pornography Law prohibits citizens from producing, producing, copying, distributing, broadcasting, importing, exporting, providing, buying, selling or renting pornographic content. Producing, producing, reproducing, distributing or broadcasting obscene content is punishable by up to 12 years in prison and a fine of up to $660,000; Downloading obscene material carries a maximum penalty of four years in prison and a $220,000 fine.

The anti-Pornography law defines pornography containing sexual activity, sexual violence, pornography, and pornography as pornography, but there is no clear definition of the standard. Given that nearly 87 percent of Indonesia's population is Muslim, the government's control of pornography is likely to be even stricter.

In November 2020, Indonesia introduced Ministerial Ministerial Regulations 5 (MR 5) to further strengthen government control over online content and user data.

MR5 regulates a wide range of subjects, including social media and other types of content sharing platforms, online shopping, search engines, financial services, data processing services, instant messaging, video, games, etc. MR5 requires private electronic system operators to submit registration information to the relevant authorities to obtain a license before they can operate in Indonesia, and requires companies to station local supervisors in Indonesia. Operators should also provide a system data interface to regulators so that they can carry out enforcement actions such as surveillance. If the enterprise refuses to provide the interface, it will face penalties such as warning, temporary ban, complete ban, and withdrawal of the license.

Article 13 of MR5 requires operators to revoke prohibited information or prohibited documents on their platforms.Prohibited information is generally referred to as any information or content that violates Indonesian laws and regulations or causes "community anxiety" or "disturbs public order." Operators should ensure that their platforms, services and websites are not used to facilitate the spread of illegal information. This provision requires operators to conduct audits and filter content on their platforms.

Indonesian Personal Data Protection Regulations

Indonesia currently has no specific personal data protection regulations, However, the EIT, Government Regulation No. 71 of 2019 on the operation of electronic systems and Transactions (GR 71), and Regulation No. 20 of the Ministry of Communications and Information Management of 2016 on the protection of personal data in electronic systems (Ministerial Regulation No. 20) all contain a number of requirements on data protection.

It is worth noting that Indonesia does not currently have strict regulations on data localization and cross-border transmission. In terms of data storage, public electronic system operators should store and manage relevant electronic systems and electronic data within Indonesia, while private electronic system operators can store or process all types of data outside Indonesia. If a company needs to transfer personal data that has been stored locally to a foreign country, it must communicate and coordinate with the MCI before doing so.

Indonesia is currently working on the Personal Data Protection Law (Draft), which may change the previous data protection regulations, and companies should keep abreast of the latest legislative developments.

03 Compliance Suggestions

In general, the Indonesian government has relatively strict regulatory requirements for bad content on the network, gambling and pornography are the most heavily regulated areas, which require special attention from the platform.

All forms of online gambling are banned in Indonesia. The EIT Law prohibits gambling-related content on the Internet. In 2020, the highest proportion of website complaints received by the Indonesian government is gambling websites, which will face IP blocking once found. Special attention should be paid to the pan-entertainment sea to avoid the appearance of gaming features containing gambling nature within the platform. At the same time, the platform itself should also increase the scrutiny of gambling content to avoid becoming a drainage tool for gambling platforms.

Pornography is also a focus of Internet regulation in Indonesia. As early as 2008, Indonesia passed the Anti-Pornography Law to regulate online pornography. In 2020, the Indonesian government received more complaints about pornography websites than any other country except gambling. The Indonesian government has a low tolerance for online pornography, and in recent years platforms such as Vimeo, Reddit and Imgur have all been briefly banned or taken down for sexual content.

In addition to content such as gambling and pornography that should be focused on prevention, there have been precedents of platforms being banned for other types of illegal content, such as inciting juvenile crime and violating local customs. Overseas enterprises should pay timely attention to user comments and complaints within the platform, do a good job in monitoring and prevention of public opinion, and ensure that the platform has a good mechanism for dealing with unexpected content security incidents.

In terms of data privacy protection, Indonesia's relevant laws and regulations on data localization and cross-border transfer are relatively relaxed, and private companies can store and process personal information outside Indonesia. However, as the Indonesian government begins to strongly support the development of the digital economy, the regulations related to the protection of consumer rights and interests in the digital economy, especially the legislation on data security, will become increasingly sound. Overseas enterprises should follow up the progress of legislation in a timely manner and adjust their operational strategies and privacy protection policies.